Breaking The Routine

By David Wood Deputy CFI (Old Sarum) – “Breaking the Routine”

By David Wood Deputy CFI (Old Sarum) – “Breaking the Routine”

Checklists and drills are jolly useful things. They jog our memories; they help us not to overlook important items. They also take off us some of the mental load at times of stress by ‘automating’ actions or sequences of actions that might otherwise absorb our thought and attention; but they have a downside.

Precisely because we sometimes do them without thinking, we also sometimes do them without noticing. And therein lies a peril. Here are some examples:

Take the common-or-garden Flapless Approach. If I had a pound for every time I’ve seen this happen then I’d be able to pay for avgas these days without wincing. The pilot turns onto base leg for a flapless approach. He knows what he’s doing. He’s relaxed and confident. He reduces power early just like he’s been taught. He remembers to take it right off and just to trickle it back on because he’s not going to have the extra drag to pull against. He trims for his flapless approach speed and he doesn’t lower flap ‘cos it’s a flapless landing, right?

He turns onto finals and calls “Finals”, just tickling the power to keep his angle of approach correct without upsetting his carefully held speed. He’s in the groove and he’s doing well. He moves his hands to the flap lever but he remembers just in time and he doesn’t lower the rest of the flap as he usually does because it’s a flapless landing.

He returns his hand to the throttle, concentrating on maintaining his approach; which is looking pretty good, by the way. And very often, perhaps eight times out of ten, he doesn’t remember to put the Carb Heat to cold. Why? Because he’s got used to doing both actions together. He’s built up a little routine. The actions have blended themselves into one little semi-automatic sequence. ‘Check up the approach, turn onto finals, make the call, set the flap, set the carb heat’. Knock out one of those actions and there is a high probability that another one or two drop out also. Don’t worry, we’ve all done it.

Here’s another. We’re at the top of the climb on a warm summer’s day. The pilot levels off and does his FREDA check just like he’s been taught. He applies carb heat. He checks the fuel: the quantity is OK, the pressure is good, the pump is now off. He checks the radio, it’s set up as he wants it. He checks the engine gauges and they all look good. Everything is going swimmingly. He’s on top of the world. He checks the DI against the compass. It’s a bit bumpy so he squints at the compass as it dances about unhelpfully. It oscillates back and forth and he wants to believe that it is still aligned with the DI but, to his annoyance, he finds that it has wandered off by ten degrees. But he can’t be sure because it just won’t stay still. Just as he decides on 10 degrees of drift he has second thoughts and thinks that maybe it’s out by 20. He is now not sure, so he decides to split the difference and he resets the DI. He is then abruptly conscious that his look-out has broken down so he quickly breaks off the FREDA check and guiltily scans the horizon, picking up a dot on the horizon that he has to watch for a moment or two before he can ascertain whether or not it is a converging aeroplane. He decides that it isn’t and he then settles down to enjoy the flight, congratulating himself on his airmanship whilst he nudges the throttle open a touch because the revs have unexpectedly dropped. The altimeter remains un-checked and the carb heat remains set to Hot until he notices his mistake at the next FREDA check.

Why did this happen? Because his little FREDA routine was compromised by having to fiddle about with the DI and then by remembering the very real need to maintain a good look-out. Both are essential actions, but both had the effect of disrupting his routine such that he didn’t notice that he hadn’t fully completed the check. Again, we’ve all done it.

And another. The pilot runs through his pre-start checks. He’s in a bit of a hurry. He flicks the fuel pump On in order to check that it pressurises the fuel system correctly. It does, but he forgets to turn it off because he is already moving on to the next item on the checklist, keen to get the engine started and warmed-up without delay. He starts up, taxies, and a few minutes later he is at the Hold running through his pre-take off checks. He gets to Fuel on his list. He checks the fuel quantity, ascertains that he’s on the correct tank for take-off, checks the pressure and then he flicks the fuel pump switch, turning it Off, before swiftly moving on to set the flaps for take off. As the aeroplane climbs out a minute or two later he congratulates himself on a quick get-away, oblivious of the fact that his smooth-running engine is now solely reliant on its mechanical pump to keep it fed with fuel. The safety net normally provided by the auxiliary pump is no longer there. Or rather, it’s still there but he’s turned it off.

Why? Because he’s come to treat the Pre-Flight Check List as an Action List. That Fuel Pump part of the sequence has become an action in which he flicks the switch; not one in which he checks the pump. And in this case, because of an earlier error he flicked the switch Off not On. It’s easily done but it could have far-reaching consequences.

And finally, just to show that none of us are immune, here’s how the same sort of thing caught me out just last month. It was towards the end of a lovely day. I had my fifth punter lined up for a trial lesson in the Moth. Actually I had the fifth and sixth, but the sixth hadn’t turned up for the detailed pre-light briefing that I always give in the classroom. So I was slightly irritated that I was going to have to brief twice and also that I was now likely to be a bit short of time as a result. It wouldn’t matter normally but I had someone’s Skills Test to do straight afterwards and I didn’t want the candidate kept waiting. So I was suddenly under a teeny bit of time pressure and my normal well-practiced routine was starting to fray.

I landed with the fifth guy, refuelled and left the Moth near the pumps. I walked my pax back to the Ops Desk and there picked up the sixth guy who had by then turned up. I decided to do a briefing for him on the hoof. After all, he looked a sensible guy. And I’ve done this trip a million times, I thought. What could possibly go wrong? So very unusually I briefed him as we walked to the aircraft, answered his many questions, showed him round the cockpit and got him strapped in and helmeted so that we were now ready to start. I turned on the fuel, flooded the inlet manifold, blew it out, locked the cowling. “Throttle Set! Switches On – Contact!”. I swung the prop and the engine caught first blade. Good old Gipsy. I walked back around and leaned into the cockpit and do all the post-start faffing about: turn on the other mag, check the oil pressure, set the engine to a comfortable tick-over, test the mags, plug back into the intercom to check that the pax was still comfortable sitting all alone in his cockpit. Then I fumbled about with my own helmet, turned on the video system, put on my jacket and finally locked the video recorder’s key-pad before tucking it into my jacket pocket. Phew; at last I was ready. I closed the throttle fully and then walked back around to the front of the aircraft to pull the chocks away. Guess what? No chocks. You could have knocked me down with a feather.

Now, I am meticulous, absolutely religious about safety when hand-swinging – particularly when handswinging my own aeroplane. I always tie back the stick, I always check that the throttle is fully closed for start, and I always put in the chocks. It’s a routine and I must have done it more than a thousand times. And in all that time I don’t believe that I’ve ever forgotten to put the chocks in. But I had this time, for sure.

Why? Well, I thought about it later that day when I reviewed the incident to myself. I believe that the seeds lay in the breaking of my well-worn routine. My classroom briefing covers the need for chocks – but I didn’t brief there as I normally do. When the Moth is at the pumps I always walk out via the concrete to pick up the big yellow chocks there – but this time I was too engrossed in briefing my pax as we walked, which I don’t normally have to do. When I was strapping him in I was conscious of the need to get started promptly so as not to delay the next guy’s exam. These are all reasons and not excuses. I’d done what I’d sworn I’d never do and I’d hand-swung an aeroplane without first chocking it. Luckily none of the other ‘holes in the cheese’ had lined up and no harm was done. The throttle was fully closed, the stick was fully back. The aeroplane didn’t move an inch. In fact no-one but me even noticed that the chocks were missing. But it was a timely reminder that none of us is immune to the perils of a broken routine.

So the message is this: checklists and routines are useful, nay they are essential. Remember that a check list is just what it says it is, it is a check list and not an action list. But in any event when, as often it must be, the check or routine is disrupted, then let a little red light go on in your mind. ‘Routine Broken: Sit Up and Pay Attention!” The normal routine that you are used to has been disrupted and something may be about to fall through the gaps. And it just might be something important. Like a set of chocks.

Bembridge Airport Account

Members planning to visit Bembridge Airport from now on can take advantage of our new agreement with the airfield that allows the landing fees to be paid 'on account', thus removing the requirement to cary the exact amount of cash needed to pay the landing fee.

Members planning to visit Bembridge Airport from now on can take advantage of our new agreement with the airfield that allows the landing fees to be paid 'on account', thus removing the requirement to cary the exact amount of cash needed to pay the landing fee.

Simply ask a member of the operations staff for the 'Bembridge landing fee sheet' which is to be filed out with your name and aircraft details and deposited in place of the usual cash payment. Your landing fee can then be paid along with your flight on return to Fairoaks and we shall take care of making the payment to Bembridge at the end of each month.

The landing fees current July 2012 are £12 (C152) and £15 (PA28 / Arrow) and the airfield is best visited on Wednesday (BST), Saturdays and Sundays when the Vectis Gliding Club, who run the airfield, are active and present on the airfield. Further details on the airfield can be found at www.eghj.co.uk

May 2012 IMC Update

The CAA issued an update to the Instrument Meteorological Conditions Rating (IMCR) in May 2012. In short, it confirms that you can continue to train towards and have an IMCR issued on your licence up until 8 April 2014.

Any UK-issued licence that has a valid IMC rating on it, prior to 8 April 2014, will retain these privileges when the licence is converted to a Part-FCL licence (the new European licence standard).

It will appear on the EASA licence as an IR(R) - a Restricted Instrument Rating. It will only be valid for use in UK airspace and will be subject to the same revalidation and renewal requirements as the current IMCR.

This is subject to any further comments that EASA may have and further details can be found in the May 2012 IMC update from the CAA.

Super Crane Lifts Manchester’s New Tower

It took one of the tallest cranes in Europe to put the finishing touches to the structure of Manchester Airport’s newly constructed £16m air traffic control tower.

It took one of the tallest cranes in Europe to put the finishing touches to the structure of Manchester Airport’s newly constructed £16m air traffic control tower.

The crane was needed to lift the 168 tonne sub-cab section 60 metres in the air, before guiding it to its finished position on the top of the tower shaft, to give the tower its finished effect on the Manchester skyline.

The sub-cab is the size of a four-storey detached house and was built on the ground before being hoisted on top of the newly built tower shaft.

Six smaller cranes assembled the 90-metre tall crane to enable it to carry out the works. The crane was brought in to the site on 25 articulated lorries.

The crane lifted the sub-cab onto the column, with two ‘banksmen’ sitting on top with radios, charged with guiding the two 10mm guide rods into place.

When the fitting out of the tower is complete the sub-cab will be home to several departments within the airport including fire watch and apron control, which guides aircraft to gates.

Now the sub-cab is in place the exterior works, such as cladding and getting the windows in place will, begin.

Andrew Harrison, Manchester Airport’s Chief Operating Officer, said: “After all the hard work and planning everyone is very excited that the final piece of the puzzle has been put in place. There is still plenty to do until the tower is ready for use and operational but the installation of the sub-cab is putting the finishing touches to an iconic element of our airport that will take pride of place on the Manchester skyline.”

Due to be completed and operational in Spring 2013, Manchester Airport’s new ATC tower is pre-let to NATS, the UK’s leading air traffic control company, which will relocate its existing Manchester air traffic control operation from its current location on top of the Tower Block building in between Terminals One and Three at the airport.

Paul Jones, NATS General Manager Manchester, said: “We have had the best view of the new tower construction and have watched with interest while the cab has been built alongside it. We are keen now to get inside the building and start fitting it out with all the latest air traffic control equipment to ensure that Manchester has a tower it can be rightly proud of.”

The control tower shaft took just nine days to rise from the ground to its current height of 60 metres. A team from construction and infrastructure company, Morgan Sindall, poured concrete continuously for 222 hours which saw the new control tower shaft increase in height at an average rate of around 27cm an hour.

Dave Smith, managing director at Morgan Sindall, says: “This is a very exciting project to be a part of and we’re delighted to have reached such a significant stage in the development. Morgan Sindall has a strong track record in the aviation sector and we’re currently on site at nine of the UK’s 15 major airports.”

Source: NATS

13 Year Old Wins Aerobatic Prize

Over the weekend 25-27 May 2012, the UK National Glider Aerobatic Contest was held at Buckminster Gliding Club where there were many fine displays by some of the best aerobatic pilots in the UK.

However, the most notable achievement was that Robbie Rizk, aged just 13, won the beginners class with a score of 82.6%. He also gained the highest score in the competition for his positioning, finesse and accurately flown manoeuvres in an ASK-21 glider.

He is the youngest person in the world ever to take part in a national aerobatics contest and had to fly with a safety pilot because he is not yet old enough to fly solo (the legal minimum age being 16)!

Robbie's father, George, is a pilot and instructor with Buckminster Gliding Club and first introduced his son to gliding at the age of 11. One of his instructors commented "Robbie is a natural pilot and shows the flair and skill that is normally seen in much more experienced pilots. He is destined to go far and could well be future 'Red Arrows' potential."

Source: Buckminster Gliding Club

Dunsfold Park Extended Hours

Dunsfold Aerodrome has been successful in their application to extend opening times during the 2012 Olympic games.

Dunsfold Aerodrome has been successful in their application to extend opening times during the 2012 Olympic games.

From the 21 July through to 15 August 2012, flying operations will be permitted between 07:00 Local and 21:00 Local each day, including weekends.

"We are delighted that the inspector recognised the important contribution to business aviation small airports like Dunsfold Aerodrome can offer and is enabling us to make the best use of our airport facilities in time for the Games," said a spokesman for Dunsfold.

"The London Olympic Games 2012 is a world event of exceptional national sporting and economic importance, strongly supported by the government, and we are very pleased that we will now have the opportunity to be able to fully engage in this momentous occasion."

Source: BBC News Surrey

Weather Getting Worse?

Just occasionally, the forecast, or the pilot’s interpretation of it, proves optimistic. We may then be presented with a dilemma when in-flight weather deterioration approaches safe limits. Of course, turning along a clearer route is the preferred option, and we should have turned back into the better weather behind us as soon as we noticed the deterioration starting.

Just occasionally, the forecast, or the pilot’s interpretation of it, proves optimistic. We may then be presented with a dilemma when in-flight weather deterioration approaches safe limits. Of course, turning along a clearer route is the preferred option, and we should have turned back into the better weather behind us as soon as we noticed the deterioration starting.

However, distractions and terrain may mean we notice the deterioration late, and the weather may be closing in behind us as well. Rather than continue into worsening weather, we need to make a positive decision to make a landing in a field before that becomes impossible. Aeroplane pilots need to make that decision early enough to select and check a suitable field then fly a circuit and land; helicopter pilots are in the fortunate situation of being able to land almost anywhere with the minimum of preparation, although we do still need to be able to control the aircraft visually. Unfortunately, human beings are not perfect. Despite all good advice, we might have been pushing our luck by flying over terrain which does not provide a safe landing area. Even over terrain which is suitable for landing, a little hesitation may take the safe areas out of our reach.

Having flown ourselves into an extremely hazardous situation, and with no safe options remaining, we have little time to make a risk assessment and judge which of the available unsafe options is the least dangerous. Rather than hit the ground, a climb under control through a gap may be the relatively safer option if it can bring us into clear air above cloud. It is not unknown for pilots to climb above some low cloud in the belief that was just a patch and in the expectation that a clear area is in front of them. Once, hopefully, above cloud we are faced with the problem of returning to the surface again safely. While PPL holders are expected to be able to use radio-navigation aids, the stress of recent events is almost certainly going to affect our flying. Rather than run out of fuel searching in vain for a hole through which to descend, if you have not already done so, call for help on 121.5 MHz as soon as you have the spare capacity.

Source: GASIL 2012/03

Hot-Air Balloon Awareness

The CAA have published Information Notice 2012/093 which intends to raise awareness of hot-air balloon operations. Included in the notice is information on their size, common locations and timings of flights as well as methods of communications.

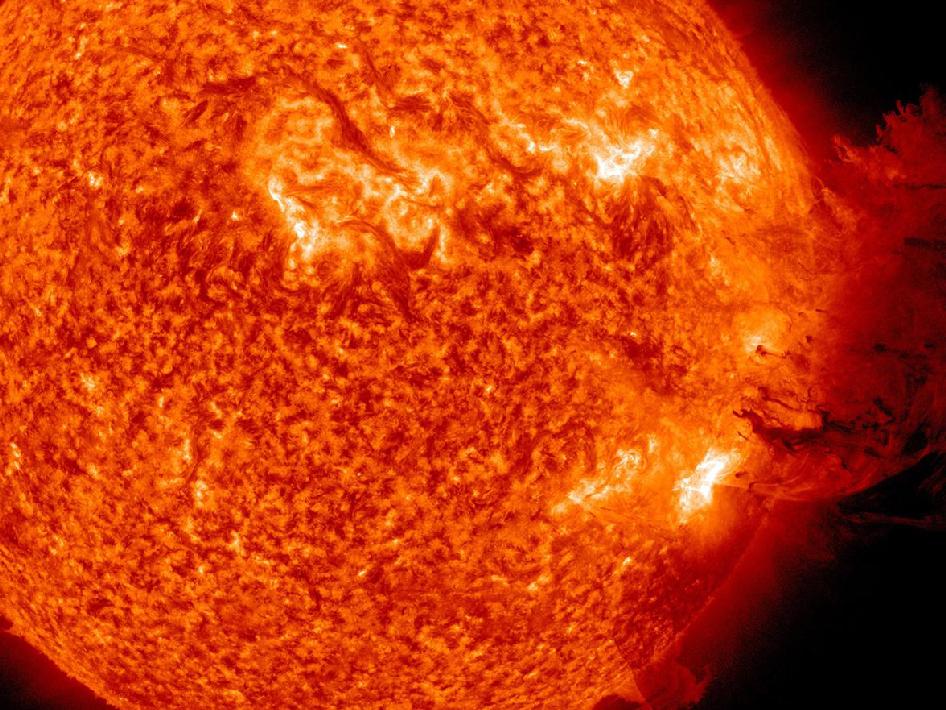

Impact of Space Weather

The Network Manager at Eurocontrol has identified space weather as a potential problem for European air traffic management, given that it is capable of disrupting aviation’s communications, navigation and surveillance systems.

The Network Manager at Eurocontrol has identified space weather as a potential problem for European air traffic management, given that it is capable of disrupting aviation’s communications, navigation and surveillance systems.

Impact on space and ground-based technology

Space weather - solar activity and solar wind in the magnetosphere, ionosphere and thermosphere - can affect the performance and reliability of both space and ground-based technology. Satellites, radio communications and even electrical power grids can be damaged by space weather. Increased radiation as a result of space weather can potentially affect flight crews, especially at higher latitudes.

Solar activity cycles

Solar eruptions can affect the earth and are more likely to occur during or just after periods of high solar activity. Solar activity has cycles of roughly eleven years and we are in one right now. The current period started in 2011 and will end in 2017.

Impact on satellites

Satellites are, unsurprisingly, vulnerable to space weather. Solar energetic particles emitted by the sun can hit satellites and cause their electronic systems to fail. Geomagnetic storms and an increase in extreme ultraviolet radiation expand the earth’s atmosphere and increase drag on low orbit satellites, making them less reliable.

Satellites have been lost - in 1989 and 2003 - because of space weather. If we have exceedingly bad space weather, experts have estimated that we could lose around half of our satellites. This would mean that we could no longer use satellite systems for navigation and surveillance.

Magnetic and solar storms

Magnetic storms can affect electrical power grids. They cause transformer saturation which reduces or distorts voltage. This can lead to transformer failure and power grid collapse. The loss of a transformer is serious: they take eighteen months to replace. In March 1989, this happened to the Quebec power grid: its long lines and static transformers made it particularly sensitive and it collapsed, leading to a nine-hour blackout and power supply problems which persisted for some time afterwards.

Space weather can affect communications, too. Solar disruptions can affect radio, especially HF (high frequency). Power failure and induced current in telecommunications grids could knock out internet access and telephones.

Solar storms can create unusually high levels of ionising radiation - up to a hundred times higher than usual. This can affect flight crews and passengers, but radiation can also impact on electronics and aircraft avionics.

Keeping a close watch

The Network Manager is in touch with specialist agencies and organisations which can give early warnings and expert information. It is keeping a close watch on the situation and ready to take instant action if anything happens.

Source: Eurocontrol News Feed

Communications Failure?

Incidents continue to occur of pilots being reportedly unable to make R/T contact with an Air Traffic Service Unit when they make their initial call after engine start, or after changing frequency. Sometimes, the pilot has believed incorrectly that a lack of response means that the ATSU is closed.

The reason for the lack of response may be that the selected frequency is incorrect. Pilots have misread published information, and on occasion have omitted to check published updates in NOTAMs and chart updates on the AIS web site www.ais.org.uk. Others have just made an error when selecting, and transmitting on ‘box2’ when the correct frequency is set only on ‘box1’ has also been known.

However, another possibility, especially when a pilot is making the initial call on a radio which has not been successfully used during recent communications on other frequencies, is a volume control set too low. Most pilots’ headsets have volume controls. There is a variety of VHF radio selectors available for GA use, and many of these are integrated into communications integration devices which have their own volume and squelch controls. There are many possibilities for a volume or squelch selector being turned too far and the pilot unable to hear.

Setting up the radios correctly is an important part of pre-flight preparation, and should avoid such a situation. Most instructors recommend setting all volume controls to the 1 o’clock position until established communications allow refinement. However, mistakes can easily be made, especially where communications pass through more than one communications device, so when we hear nothing after our initial call on a frequency we should seek out possible causes before assuming we can continue safely.

If we can hear other transmissions, it could be our transmitter at fault, but if we hear nothing we should check the frequency set, then check all volume controls. If all is correctly set, after another attempt at an initial call we also ought to consider the possibility that our transmitter is stuck ON, and try listening on another frequency. These checks take time which we should be prepared to take. Initiate calls early, and remain in a safe place until the problem is resolved, or if it cannot be resolved, follow the communications failure procedure as published for the airspace or aerodrome, making blind calls in the correct places. CAA Safety Notice 2012/002 reminds us of where to finds these published procedures, and reminds us of some possible problems if the radio fails on the approach to land.

Source: GASIL 2012/03